Key points about pyloric stenosis

- the pylorus is the passage that connects the lower part of the stomach to the rest of the bowel

- all food leaving the stomach has to go through the pylorus

- when a baby has pyloric stenosis, the muscles in the pylorus have become too thick to allow milk to pass through it

- the first symptom is usually forceful or projectile vomiting soon after feeds

- if your baby has pyloric stenosis, they will need surgery

- if your baby is dehydrated from vomiting, they will need treatment with intravenous (IV) fluids before surgery

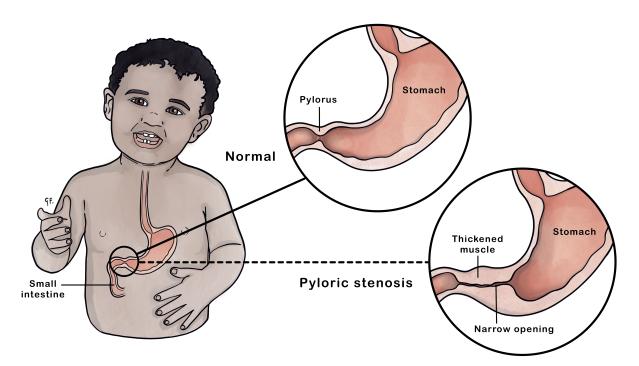

What is pyloric stenosis?

Pyloric stenosis (also called infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis) is a narrowing of the pylorus - the passage that leads from the stomach to the small intestine. When a baby has pyloric stenosis, the muscles in the pylorus have become too thick to allow milk to pass through it. This usually happens in the first 6 weeks after birth.

Causes of pyloric stenosis

Experts do not know exactly what causes the thickening and enlargement of the muscles in the pylorus.

Pyloric stenosis affects more boys than girls and tends to run in families.

Signs and symptoms of pyloric stenosis in babies

Vomiting

- vomiting of feeds, usually within 30 minutes of a feed that typically starts happening 4 to 6 weeks after birth

- vomiting tends to get worse until your baby is vomiting after every feed

- forceful vomiting that can be projected 1 metre out of the mouth (projectile vomiting)

- the vomit is usually yellow, the colour of curdled milk

- occasionally, the vomit may have small brown specks of old blood in it

- despite the vomiting, pēpi (babies) are usually keen to feed (because they are hungry)

Weight loss

- failure to gain weight or weight loss

Being upset

- they remain hungry because they vomit up their feeds

Dehydration

- dry mouth and tongue

- fewer wet nappies or not doing as much wee as usual

- unusual sleepiness, difficult to wake (lethargic) if the vomiting has been going on for several days

- sunken eyes

- the soft spot on the top of the head (anterior fontanelle) is more sunken than normal

Ripples

- sometimes, you can see ripples or waves move across the stomach (abdomen) after a feed

- these are muscle contractions (peristalsis) as the stomach tries hard to empty milk into the small intestine

Less poo

- less poo

- poos can be smaller from less food getting past the thickened pylorus

When to get medical help for your baby

If you think your child has pyloric stenosis, see a health professional straightaway. Do not delay, as young pēpi who are not able to feed normally can become unwell quickly.

Diagnosing pyloric stenosis

The health professional will ask about your baby's symptoms. They may ask about:

- patterns of feeding and vomiting

- the colour of your child's vomit

- any weight loss or failure to gain weight

The health professional may try to feel a mass or lump (the thickened pylorus) over your baby's stomach.

Your baby might need some investigations or tests.

An ultrasound scan of the abdomen

An ultrasound scan of your baby's tummy may show the thickened pyloric muscle.

A test feed

A health professional may give your child a small feed. This is to help your baby relax enough to allow the health professional to feel if there is a lump in your child's tummy.

Blood tests

In almost all cases, your baby will need a blood test. Abnormalities of the blood are corrected before surgery.

A barium meal

A barium meal is a special type of x-ray. Only a small number of pēpi need it. A health professional will give your baby a small amount of chalky liquid (barium). Your baby will then have an x-ray of their abdomen, which will show the passage of the barium through the gut. Any blockage or narrowing will show on the x-ray.

Managing pyloric stenosis

The treatment for pyloric stenosis is an operation called a pyloromyotomy. A pyloromyotomy involves a surgeon cutting through and spreading the thickened and enlarged muscles of the pylorus. This helps to relieve the blockage (obstruction). Surgeons can use different approaches for this surgery. The surgeon will discuss which approach they will use before your child has surgery.

Your child will have the surgery under general anaesthetic (GA), and they will be completely asleep.

Laparoscopic or 'keyhole' surgery

Laparoscopic or 'keyhole' surgery is where the surgeon makes 3 three tiny cuts over the tummy. This is the most common technique.

Open surgery

Surgeons use either an umbilical approach or make a small cut above the pylorus.

Umbilical approach

The surgeon makes a cut in the tummy button (umbilicus) itself.

Incision overlying the pylorus

The surgeon makes a small cut directly over the pylorus.

See the page on anaesthetic to learn more about what it involves.

What happens before the operation for pyloric stenosis

Fasting

Your child may not be able to eat or drink anything for a period of time before their surgery.

Nasogastric tube

Some pēpi may need a nasogastric tube. This is a tiny plastic tube inserted through their nose and down into their stomach. This allows the health professioal to remove the stomach contents, which can help stop their vomiting.

IV drip

Your baby will need an intravenous (IV) drip before the operation. Pēpi with pyloric stenosis usually have abnormal levels of several important substances in their blood (called electrolytes). These levels must return to normal before the operation. This usually takes several hours and can even take a day or two.

Talk with the surgical team

Your baby's surgical team will explain what will happen during the operation. They will talk you through any other treatment that your child may need. You will have the opportunity to ask questions.

What happens after the operation for pyloric stenosis

Your baby may need medicine to help with pain after the operation. This may be through an intravenous (IV) drip.

For the first few hours, your baby will continue to have fluids through the drip. This will give the stomach time to start healing. Your baby can start feeding small amounts after about 12 hours.

Your baby may still vomit some of the feed, but this won't be forceful or projectile vomiting as before. The vomits or spills will decrease over several days. You will be able to take your baby home once they are feeding normally and are well.

Caring for your baby at home after treatment for pyloric stenosis

Your baby may still be sore for a day or two once you go home. Your doctor will suggest medicines to help with pain after you leave the hospital. Handle your baby normally.

Usually, you can bath your baby any time after the surgery. Check this with your surgeon.

Keep an eye on the wound. Take your baby to a health professional if you notice any signs of infection around the wound. Signs of infection include:

- redness around the wound

- oozing or pus coming from the wound

- swelling around the wound

- a fever

- your baby stops feeding

Possible complications of treatment for pyloric stenosis

All surgery comes with some potential risks, such as bleeding during and after the surgery. There is a small chance of damage to the delicate lining of the bowel, but if this happens, the surgeon usually finds and fixes this during surgery. There is also a small risk with having an anaesthetic. You will speak to the surgeon and anaesthetist before the surgery so you can ask any questions you have.

Pyloric stenosis can happen again, but this is rare.

Acknowledgements

Illustration by Dr Greta File. Property of KidsHealth.